Evaluations: Clones, Teaming and Independence Criteria 7

CHPV, Clones and Teaming (continued)

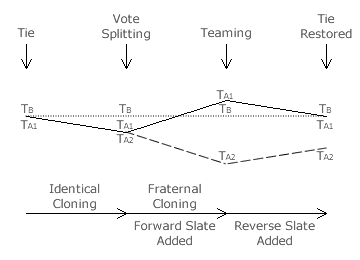

The figure opposite illustrates the effects of the introduction of the identical clones, converting them into fraternal clones using a forward slate and then combating this with a reverse slate. Notice that the tally for B is unchanged throughout as the voter preferences for or against B are unaltered. Party A cannot succeed merely by adding a clone as identical cloning results in vote splitting.

It has to issue a forward slate to transform these clones into fraternal ones to gain victory. However, this very act effectively exposes A2 as being the inferior fraternal clone to the superior one A1. This then alerts and enables party B to issue a reverse slate to counteract the teaming by A and to re-establish the equal parity between them. Party B should not and does not need to respond by adding any clones of its own.

Suppose party A thinks that adding a third fraternal clone A3 will break the tie. Provided party-slate B is maintained as the exact reverse of the forward (now three-candidate) party-slate A, then the critical tie between B and A1 is rigorously retained.

It makes no difference how many clones A nominates as all B has to do to retain parity is to reverse the slate; since both A1 and B are supported as first preference by half of the voters and as last preference by the other half. With this two-way tie there is no winning clone strategy for A provided B adheres to its tit-for-tat retaliation using slate reversal.

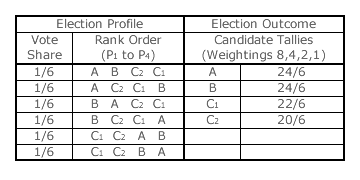

If there was a three-candidate critical tie instead, would cloning by one party (say C) then achieve unjust victory? The table opposite defines the profile and outcome for this situation. Before fraternal cloning (replacing C1 and C2 with just C in the table), then each candidate has one third of first, second and third preferences and an equal tally.

After cloning, the cloning party (C) now not only fails in its teaming attempt but actually loses. It even leaves A and B unaffected at equal parity. The reason that C now loses is that two reverse slates are opposing the one forward slate. For a four-candidate critical tie, there would then be three reverse slates against the one forward slate and C would lose by a even greater margin.

For two-party ties, a forward slate is exactly counterbalanced by a reversed one. However, for ties between three or more parties, the one forward slate is overwhelmed by the more numerous reversed slates.

For single-winner elections, a party should only nominate one candidate. By introducing identical clones, a party will only inflict harm on itself. By nominating fraternal clones, a party may hope to gain an unfair advantage but this can always be thwarted by slate reversal. Unless it is a straight two-way contest, attempts at teaming can again result in the cloning party inflicting self-harm. As truncation is freely available to voters, not ranking any opposition clone candidates is an even more effective means of punishing that clone set.

There is therefore no incentive for a party to nominate either identical or fraternal clones in any CHPV election. Indeed, there is potential self-harm in cloning. Nor is there any incentive for a party to retaliate using cloning. CHPV does not itself automatically prevent or combat vote splitting or teaming. However, CHPV voters are able to stop parties from gaining unfair victory through teaming.

- As a voting system, CHPV is not independent of clones.

- However, CHPV voters are always capable of successfully thwarting teaming attempts.

- Also, in CHPV there is never any incentive to clone as cloning is either unsuccessful or self-harming; provided slate-reversal retaliation is enacted where necessary.

Proceed to next section > Evaluations: Teaming Thresholds

Return to previous page > Evaluations: Clones & Teaming 6